Predicting Sales Profits and House Prices using Simple and Multiple Linear Regression

Linear regression is one of the most common supervised machine learning methods, where we are basically taking input variables and trying to fit the output onto a continuous expected result function. Generally, there are two types of Linear regression - simple linear regression (sometimes called univariate linear regression) and multiple linear regression. The former is used when you want to predict a single output from a single input, while the latter is used when you want to predict a single output form multiple inputs.

Simple Linear Regression

We will first implement linear regression with one variable to predict profits for a food truck. Suppose you are the owner of a restaurant franchise and are considering different cities for opening a new outlet. Assuming the chain already has trucks in various cities and you have data for profits and populations from the cities. You would like to use this data to help you select which city to expand to next. In this problem, we will fit the linear regression parameter, , to our dataset using gradient descent - specifically the batch gradient descent algorithm, where the objective is to minimize the cost function

where the hypothesis is given by the linear model, with set at 1.

In batch gradient descent, each iteration performs the update

With each step of gradient descent, our parameter come closer to the optimal values that will achieve the lowest cost .

Let us visualize the data to help us better understand the problem!

% Plot the data

plot(x, y, 'rx', 'MarkerSize', 10);

% Set the y-axis label

ylabel('Profit in $10,000s');

% Set the x-axis label

xlabel('Population of City in 10,000s');

Figure 1: Visualizing the scatter plot

Using =0, learning rate =0.01 and iterations = 1500, the computed cost value will be approximately at 32.07. Using these settings, we will be able to fit our model into our dataset like shown in Figure 2.

% Add a column of ones to x

X = [ones(m, 1), data(:,1)];

% Initializing fitting parameters to 0

theta = zeros(2, 1);

% Settings

iterations = 1500;

alpha = 0.01;

Running Gradient Descent ...

ans = 32.073

plot(X(:,2), X*theta, '-')

legend('Training data', 'Linear regression')

Figure 2: Fitting into our dataset

Based on how our model fits, we would be able to predict our profits given different input, such as:

predict1 = [1, 3.5] * theta;

predict2 = [1, 7] * theta;

Theta found by gradient descent: -3.630291 1.166362

For population = 35,000, we predict a profit of 4519.767868

For population = 70,000, we predict a profit of 45342.450129

Whenever we want to better understand the behavior of our cost function , it is always useful to plot it and visualize, either using a surface or contour plot, because it gives us a better sense on how varies with changes in and .

Figure 3: Visualizing cost function using surface

Figure 4: Visualizing cost function using contour, showing minimum

Multiple Linear Regression

Another widely used variation of linear regression is multiple linear regression. In this example, we will implement linear regression with multiple variables to predict the prices of houses! Suppose we are trying to sell our house and we would like to know what a good market price would be, one way to do this is to first collection information on recent houses sold and make a model of housing prices. Our dataset contains three columns which consist of the size of the house (in sq. ft.), the number of bedrooms and finally the price of the house. The only difference of multiple linear regression to simple linear regression is that there is one more feature in the matrix X. The hypothesis function and the batch gradient descent update rule remain unchanged.

But here comes a problem, all these data may varies hugely in range (imagine comparing the size of the house to the number of bed rooms) and this might slow down our gradient descent process. We can speed up gradient descent by having each of our input values in roughly the same range. This is because will descend quickly on small ranges and slowly on large ranges, and so will oscillate inefficiently down to the optimum when the variables are very uneven. This can be achieve via mean normalization + feature scaling where we subtract the mean value of each feature from the dataset and scale (divide) the feature values by their respective ‘standard deviations’.

% mean normalization + feature scaling

mu = mean(X_norm);

sigma = std(X_norm);

for i = 1:size(X,2)

X_norm(:,i) = (X_norm(:,i) - mu(i))/sigma(i);

end

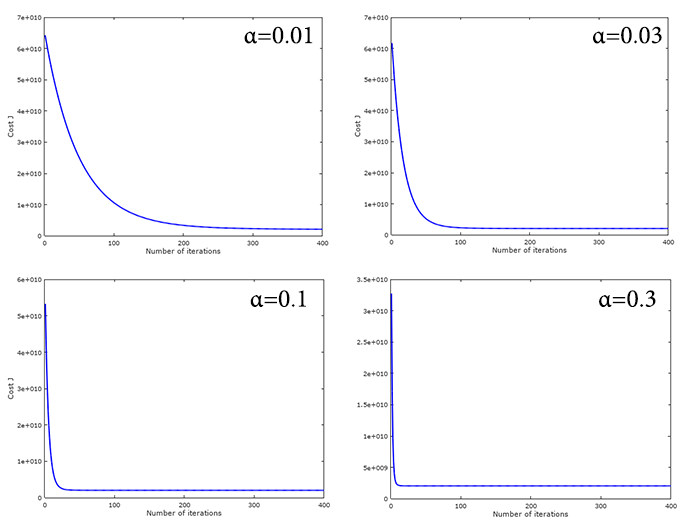

Once you implemented these, it is also important to check whether gradient descent is converging correctly by plotting the convergence graph as shown in Figure 5.

plot(1:numel(J_history), J_history, '-b', 'LineWidth', 2);

xlabel('Number of iterations');

ylabel('Cost J');

Figure 5: Graph of convergence of Cost J across 400 iterations with

In Figure 6, we tested using different learning rate, to study the effects it has towards the convergence graph. It is prudent that with a higher , cost J tends to converge much faster. But do keep in mind that using a high might affect the solution in a way where it might not be able to arrive at the global optimum since the is a high possibility of overshot. On the contrary, using a low value will increase the chance of reaching the global optimum, but it will be computational expensive, since gradient descent will be taking one small step in each iteration to reach the global optimum.

Figure 6: Comparing Cost J convergence with different learning rate, .

Figure 6: Comparing Cost J convergence with different learning rate, .

With = 0.01 and iterations = 400 we are able to compute the following

Running gradient descent ...

Theta computed from gradient descent:

340412.659574

110631.050279

-6649.474271

And given the size of a house of 1650 sq-ft with 3 bed rooms, our model predicted a price of 293081.

Predicted price of a 1650 sq-ft, 3 br house (using gradient descent):

$293081.464335

To wrap it up, it is important to understand that most real-world analyses have more than one independent variable. Therefore, it is likely that you will be using multiple linear regression for most numeric prediction tasks. The strengths and weaknesses of multiple linear regression are shown in the following table:

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| By far the most common approach for modeling numeric data | Makes strong assumptions about the data |

| Can be adapted to model almost any modeling task | The model’s form must be specified by the user in advance |

| Provides estimates of both the strength and size of the relationships among features and the outcome | Does not handle missing data |

| Only works with numeric features, so categorical data requires extra processing | |

| Requires some knowledge of statistics to understand the model |